By Dr. Tan Kheng Khoo

An ordinary man is a Buddha; illusion is salvation. A foolish thought, ----- and we are ordinary, vulgar, stupid. The next enlightened thought, -------and we are the (exalted, poetical, and wise) Buddha.

Huineng

I do nothing meritorious,

But the Buddha-nature manifests itself.

This is not because of my teacher’s instruction,

Nor is it due to any attainment of mine.

Chang Hang Chang

The mind is not the Mind, and becoming enlightened is not becoming enlightened.

Obaku

Before your father and mother were born, what was your original face?

Daito Kokushi

While deluded, one is used by this body; when enlightened, one uses this body.

Bunan

![]()

Introduction

This essay is to go into the historical sequence of how Zen Buddhism came about. It also intends to analyze the philosophical tenets of Zen Buddhism. One has to start from the source, which is Gautama Buddha. From the beginning in Northern India, Gautama became enlightened and he started to teach how to deal with the problems of life. Then Buddhism was brought by Bodhidharma to China about 600 years after Buddha passed away. In China with Buddhism as the father, the indigenous Taoism as the mother, Zen Buddhism was begotten. To some extent, Confucianism also played a part in the ethics and morality of Zen. Six hundred years after Bodhidharma came to China Zen Buddhism went over to Japan. Some sort of marriage also took place there. Chinese Zen Buddhism merged with Japan’s indigenous religions. These were the Shin, Nichiren, Tendai, Shingon and Jodo. All these together amalgamated with Chinese Zen to produce Japanese Zen. In Japan Zen also split into Rinzai and Soto sects.

In India the states of mind during meditation is designated ‘Dhyana’. In Pali it is called ‘Jhana’. It is this ‘Jhana’ that eventually became ‘Chan’ in Chinese. In Japan this ‘Chan’ became Zen. In other words Zen literally means meditation.

Today, Buddhism is divided into Theravada and Mahayana. Theravada Buddhism prevails in Ceylon, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore. Tibetan Lamaism and Buddhism of Korea, China, Mongolia and Japan represent Mahayana Buddhism. Of course, in the present day, there is quite an admixture of Mahayana and Theravada in the South East Asian countries. Interestingly, the difference between Zen and Tibetan Buddhism is far greater than the difference between Zen and Theravada Buddhism. However, the dividing principle here is Arahatship of Theravada and the Bodhisattvahood of Mahayana.

We have to trace the historical trend of how Indian Buddhism became Zen. It was said in some quarters that Zen began when Buddha held up a flower and Mahakasyapa smiled. This silent smile represents transmission from Gautama Buddha to the first Indian Zen Patriarch. There were twenty-eight Indian Zen patriarchs all told. Bodhidharma was the 29th Indian Zen Patriarch and became the first Chinese Zen Patriarch.

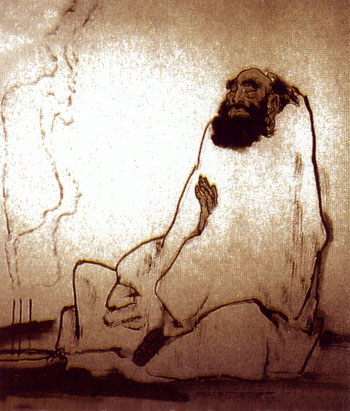

Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma was the First Chinese Zen Patriarch to have brought Buddhism to China. His Buddhism had a fair amount of Hinduism in it. There were still some strains of Upanishads in his mental makeup. He was born in 440 AD in Kanchi in South India. He was a Brahmin by birth and was the third son of King Simhavarman. He was converted to Buddhism at a young age, receiving the Dharma from Prajnatara, who also asked him to go to China. Bodhidharma left the port of Mahaballipuram at the east coast of India and skirted around the Malay Peninsula for 3 years to arrive in South China around 475 AD.

Buddhism had already arrived in China as early as 65 AD and since then tens of thousands of Indian and Central Asian monks had journeyed to China by land and sea. By the time Bodhidharma arrived in China, there were approximately 2,000 Buddhist temples and 36,000 clergy in the South. In the North a census counted 6,500 temples and 80,000 clergy. Less than 50 years later the figures rose to 30,000 temples and 2,000,000 clergy.

According to legend, Bodhidharma also brought tea to China. In order not to fall asleep, he cut out his eyelids, which fell to the ground. On the ground where the eyelids fell tea bushes grew. Another legend quoted that he crossed the Yangtze on a hollow reed and settled in the Northern Wei capital of Pingcheng. When the Emperor Hsiao-wen moved his capital to Loyang, most of the monks followed suit, as they were dependent on royal patronage. In the year 496, the Emperor ordered the construction of the Shaolin Temple on Mount Sung. It was here in Shaoshih Peak that Bodhidharma spent nine years meditating facing the wall in a cave. He also must have instructed his disciples in some form of yoga, but not specifically teaching any form of martial arts. He had only a few disciples, and one of them was Huike, to whom he entrusted the bowl and robe. Soon after this transfer he died in 528, apparently poisoned by a jealous monk. Again legend has it that 3 years later an official met him walking in the mountains of Central Asia. He was carrying a staff, from which hung a single sandal, telling the official that he was going back to India. In respond to sundry rumors, his tomb was opened and only a single sandal was found. There was no body!

The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma

In his time, there were basically two roads that lead to the Path: reason and practice. To enter by reason means to realize the essence through instruction and to believe that all living things share the same true nature. To enter by practice refers to four practices: 1) suffering injustice, 2) adapting to conditions, 3) seeking nothing, and 4) practicing the Dharma.

1) Suffering injustice. Because of past karma one suffers in this life. With understanding one should accept the injustices because of one’s evil deeds in one’s past lives. Keeping harmony with reason, one enters the Path.

2) Adapting to conditions. The suffering and joy we experience depend on conditions of our fruits planted in the past lives. One should not be happy or sad as these conditions will end. The mind, however, remains unmoved. If this is realized, one enters the Path.

3) Seeking Nothing. Craving or seeking is suffering. All things contain nothing as their true essence. The wise does not desire and is not attached to anything. They are on the Path, seeking nothing.

4) Practicing the Dharma. The truthful Dharma says that all natures are pure and empty. “The Dharma includes no being because it’s free from the impurity of being, and the Dharma includes no self because it’s free from the impurity of self”. The wise, that believes this truth, practices charity, giving away all things including self without bias and vanity of the giver. They also teach others this practice of the way to enlightenment. This is practicing the Dharma.

Of course Bodhidharma taught a lot of things, but we will just study two of his sermons: Bloodstream Sermon and Wake-up Sermon. These two will give an indication of the essence of his teaching. Both sermons are taken from the “The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma” translated by Red Pine.

Bloodstream Sermon

The mind is Buddha, nirvana or enlightenment. This is the reality of self-nature. The mind is Buddha-nature. Whoever sees his own nature is a Buddha. It is useless invoking Buddhas, reciting sutras, making offerings and keeping precepts, if you don’t see your own nature. Running around all day looking for a Buddha is a thorough waste of time. Just realize your own nature. There is no Buddha outside your own Buddha-nature. The nature of this mind is basically empty, neither pure or impure. This nature is free of cause and effect. This Buddha-nature needs not practice or realize. It does no good or evil; it does not observe precepts. It is not lazy or energetic. It does nothing. A Buddha is not a Buddha. Without seeing your nature, you cannot practice thoughtlessness all the time. This mind or Buddha-nature is not the sensual mind. It never lived or died throughout the kalpas. The mind has no form and its awareness no limit. “ A tathagata’s forms are endless. And so is his awareness”. Our mind is the same as the mind of all Buddhas. “Everything that has form is an illusion”. “ Wherever you are, there is a Buddha.” We’ve always had our Buddha-nature. Our mind is the Buddha: don’t worship a Buddha with a Buddha. Once a person realizes his mind or Buddha-nature, he stops creating karma.

Your mind is like space: you cannot grasp it. It has no cause or effect. No one can fathom it. This mind is not outside the body, which has no awareness. It is not the body that moves; it is the mind that moves.

This sermon speaks of the Buddha-nature, which is empty and has no form. We always have had the Buddha-nature within us, and this sermon also describes in detail what is the Buddha-nature. But it does not teach us how to see our Buddha-nature.

Wake-up Sermon

‘Detachment is enlightenment because it negates appearances’. Buddhahood means awareness.

To leave the three realms (poisons) means to go from greed, anger and delusion to morality, meditation and wisdom. The three poisons are also buddha-nature. Not thinking of anything is Zen. To see emptiness and no mind is to see Buddha. To give oneself is the greatest charity and to transcend motion and stillness is the highest meditation. Mortals keep moving whilst arhats stay still. Using the mind to look for reality is delusion. Not creating delusion is enlightenment. No affliction is nirvana.

No appearance of the mind is the other shore. When deluded this shore exists. When you wake up, it does not exist. Those who discover the greatest of vehicles stay on neither shore.

Delusion means mortality. Awareness means Buddhahood.

The impartial Dharma is only practiced by great bodhisattvas and Buddhas. To look on life and death as different and motion is different from stillness is to be partial. To be impartial is to take suffering as no different to nirvana, as both natures are empty. That means when suffering one is in nirvana. Nirvana is beyond birth and death and beyond nirvana. When the mind stops moving it enters nirvana, which is an empty mind.

When thought begins you enter the three realms of desire, anger and form. When thought ends you leave the three realms.

Mortals think the mind exists whilst arhats say they don’t, but bodhisattvas and Buddhas say that mind neither exists nor does not exists. This is the Middle Way.

Those who perceive the existence and nature of phenomena and remain unattached are liberated. Not to be subjected by affliction of appearance of phenomena is liberation. Looking at form without the arising of the mind is the right way to look. When delusions are absent, the mind is the land of Buddhas. When delusions are present, the mind is in hell. Bodhisattvas see through delusions by using the mind to give birth to mind, they remain in Buddha land. When thought arises there is good and bad karma, heaven and hell. Where there are no thoughts, there is none of these.

When one is in nirvana, one does not see nirvana, because the mind is nirvana. One is deluding oneself, if one sees nirvana outside one’s own mind.

Suffering gives rise to Buddhahood: your mind and body are the field. Suffering is the seed, wisdom the sprout, and Buddhahood the grain.

The Buddha is like fragrance in a tree: Buddha comes from a mind free of suffering, but the mind does not come from Buddha. Whoever wants to see Buddha must see the mind first. Once you have seen the Buddha, you forget about the mind. However you cannot have Buddha without a mind. If you fill a land with impurity and filth, no Buddha will appear. Like ice and water, mortality and Buddhahood are the same nature. To be in the three realms is in mortality: to be purified of the three poisons is Buddhahood. When a mortal is enlightened, he does not change his face: he knows his mind through internal wisdom and takes care of his body through external discipline.

Mortals liberate Buddhas because afflictions create awareness. And Buddhas liberate mortals because awareness negates affliction. Buddhas regard delusion as their father and greed as their mother. Delusion and greed are different names for mortality.

When deluded you are on this shore. When aware you are on the other shore. Once you know that your mind is empty and you are beyond delusion and awareness: the other shore does not exist. The tathagata is not on either shore. Neither is he in midstream. Arhats are in midstream. Mortals are on this shore. Buddhahood is on the other shore.

Individuals create karma; karma does not create individuals. They create karma in this life and receive their reward in the next. Only someone who is perfect creates no karma and receives no reward. When you create karma, you are reborn along with your karma. When you don't create karma, you vanish along with your karma. That means karma has no hold on him, who does not create karma. The present state of mind sows and the next state of mind reaps.

“When you see that all appearances are not appearances, you see the tathagata” says the sutras. The myriad doors of the truth all come from the mind. When appearances of the mind are as transparent as space, they are gone. When mortals are alive, they worry about death. When they are full, they worry about hunger. Sages don’t consider the past, neither do they worry about the future. They also do not cling to the present. They simply follow the Way from moment to moment.

In this sermon, Bodhidharma advised us not to indulge in the three poisons of greed, anger and delusion. In addition, one must empty one’s mind presumably through meditation. When one sees that the mind is truly empty, one is free of delusion and awareness. One is in Nirvana.

The Other Patriarchs

Huike (Eka) was the Second Patriarch. Next, Sengtsan received the bowl and robe from Huike, and became the Third Patriarch. At this time there were periodic persecutions of Buddhism with wholesale burning of sutras and images. Sengtsan, in order to avoid persecution, wandered all over the country for fifteen years. Sengtsan also wrote the first treatise on Zen----Hsinhsinming. This is a brilliant recording of the experience, knowledge, and conviction of the Buddha-nature. This is a description of one’s Believing Mind in oneself where no doubt exists. It is deep, profound and famous. Sengtsan died in 606 AD. In 592 AD he met Taohsin, who became the Fourth Patriarch.

After Taohsin came Hungjen, the Fifth Patriarch. Hungjen died in 675 AD. He was renowned for having two famous and contentious disciples named Huineng and Shenhsiu. Huineng was the notable, illiterate Sixth Patriarch. Huineng initiated the ‘philosophy of living’ in Zen in the 7th century. His Zen is neither Indian nor Chinese. His Zen is super-national, almost superhuman, but not supernatural.

Huineng

Huineng was born in 637 AD already an enlightened being and died in 713 AD. He was re-enlightened on hearing the Diamond sutra recited in a house to which he had just delivered some firewood. He was enlightened once again when the Fifth Patriarch, Hungjen, repeated the same sutra. Huineng never went to school, but I suspect that he was not as illiterate as history would like to make him so. He was born knowing and he knew that he knew. Zazen was the result and not the cause of his enlightenment. He taught the gospel that the eye can see itself. The real actor is the action. Huineng’s Platform Sutra (Prajnaparamitahridaya) is very long. However, two poems by Shenhsui and Huineng embody the whole history of Buddhism. Huineng was 24 years old when he arrived at the Wang-mei monastery of Hungjen, the Fifth Patriarch. He was asked to pound rice in the barn. Hungjen (601-674) had asked his disciples to compose a poem to indicate their degree of enlightenment. His foremost disciple, Shenhsui (606-706) composed this gatha and wrote it on the temple wall:

The body is the Bodhi tree (enlightenment)

The mind is a clear mirror standing.

Incessantly wipe and polish it;

Allow no grain of dust to cling.

Huineng had Shenhsui’s gatha read to him. Unimpressed by it, Huineng composed one himself. He asked the temple boy to write it on the temple wall:

The Bodhi is not like a tree,

The clear mirror is nowhere standing.

Fundamentally not one thing exists:

Where, then is a grain of dust to cling?

Hungjen erased Huineng’s poem, stating that it was far from enlightenment. He then asked Huineng to his rooms the following night. On that night, Hungjen handed over to him the robe and alms bowl, making Huineng the Sixth Patriarch. Huineng was also advised to flee to the south, crossing the Yangtze River that same night. Huineng did that straightaway.

Some features of Huineng’s teaching.

Huineng had some critical comments on zazen. He criticized Shenhsui’s advice to his own disciples to concentrate ‘their minds on quietness as long as possible.’ To this advice, Huineng had this to say: “To concentrate the mind on quietness is a disease of the mind, and not Zen at all.” When asked how he could understand the meaning of the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, he answered: “The profound meaning of all the Buddhas has no connection with words and letters.” “The right way to recite a sutra is according to its meaningless Meaning. To put a meaning into it is all wrong.”

Huineng was at the entrance of a monastery in southern China, and this was what he heard and saw:

The temple flag was blowing in the wind. Two monks were arguing about it.

One said: “The flag is moving.”

The other said: “The wind is moving.”

Thus they argued back and forth, reaching no agreement. Then the Sixth Patriarch said: “It is not the wind that’s moving; it is not flag that’s moving----- it’s your mind that is moving.”

The two monks were awe-stricken (with enlightenment).

As a matter of reality, the mind is also not moving!

Upon his return to southern China, Huineng lived in seclusion in the forests and mountains for sixteen years. Later he lived in the monastery Pao-lin in Ts’ao-chi, Canton. Huineng passed away, seated in the lotus position, on August 28, 713 AD at Kuo-en Temple in Hsin-chou. His death position tells us much more about his stand on zazen than any other postulations of his.

Huineng, thus, became celebrated as the new founder of the “Southern Zen of Suddenness.” This contrasts with Shenhsui’s “Northern Zen of Gradualness” where the usual practice was gradual meditation, which means purifying one’s mind.

The Three Schools of Zen

The 6th Patriarch had many disciples, five of whom were prominent: Seigen, Nangaku, Kataku, Nanyo and Yoka. The Rinzai and Soto schools were both derived from two of these five Great Masters: Nangaku and Seigen. Eisai founded the Rinzai and Dogen initiated the Soto sect. Besides these two sects, Japanese Zen has another sect: Obaku (Hwang-po). This is the smallest school and was introduced by the Chinese monk, Yin-yuan (1592-1673). His teaching was very much like the Rinzai but he emphasized zazen and repeated invocation of Buddha Amitabha to be reborn in the Pure Land. From these three major sects, they are subdivided into 24 subsects.

Japanese Buddhism

Although Buddhism was introduced to Japan as early as 522 AD, it was Prince Shotoku who established Buddhism in Japan. He ruled Japan from 593 to 622 AD. He incorporated Buddhist teachings into the political and social life of Japan. Buddhism was proclaimed as the state religion. The foundation of Buddhism was instituted as a temple, an asylum, a hospital, and a dispensary. He also instituted spiritual harmony by enunciating the Three Treasures: The Buddha, The Dharma and The Sangha are to be revered as the ultimate truth. At this period he allowed Buddhism to transcend the indigenous Japanese Shitoism. In 604 AD he promulgated the first constitution of Japan in which he stated that a single monarch implied equality of all the people. He pronounced that Buddha was the saviour of all mankind.

A permanent capital in Nara was established in 710 AD and this act promised two centuries of Buddhist growth and influence in all walks of social life. Temples and monasteries were built for religious functions and communications, and these led to accumulations of wealth. At the beginning this money went to social and educational purposes, but later it led to corruption of the monkhood. A great historical event came as the dedication of the Central Cathedral in Nara. It was known as the Todai-ji. Furthermore, a magnificent temple dedicated to the Buddha Vairocana made the relationship of the government to Buddhism even closer. It was during this Nara period that the merging of the three major schools of spiritual teachings took place: Shinto, Buddhism and Confucianism. Shinto happily joined the other two because it was primarily a tribal cult with a belief in protecting deities functioning through local rituals. Confucianism supplied the ethical teachings basing on virtue. The ancestor worship and filial piety of Confucianism were easily absorbed into the Hindu-influenced Buddhism’s veneration of the dead. Then corruption set in. Monks became rich and powerful. A breakdown with reformation was inevitable.

Reformation was precipitated when the capital was transferred from Nara to Kyoto in 794 AD. Two brilliant monks rose up to entrench Japanese Buddhism with the support of the state. Saicho (767-822) and Kukai (774-835) tried to develop new schools of Buddhism infusing Chinese Buddhism in their attempts. Saicho (Dengyo-daishi) founded a seat of learning at Mount Hiei not far from Kyoto. Here he introduced the scriptures and treatises of the Tendai School of Chinese Buddhism. These teachings emphasized the universality of attainment of Buddhahood, embracing the lowest of beings, including beasts and insects. His concept of universal salvation and his ability to conduct mystical ceremonies won him government support. Saicho of Mount Hiei then became the supreme Buddhist power before the decay in the twelve and thirteen centuries. At one stage he was even able to control state affairs.

Kukai (Kobo-daishi) also visited China and brought back a new form of Chinese Buddhism—Shingon. This has a mixture of mysticism and occultism and it was situated fifty miles from Kyoto on Mount Koya. Kukai’s reputation as a powerful occultist earned him the respect of all and sundry---influential nobles and simple folks alike. Eventually Shingon became the strongest amidst all Buddhist schools because of the esoteric aspects of its teachings.

These ritualistic and superstitious aspects of Shingon Buddhism became even more powerful after Kukai died. Wealth and power were the perfect ingredients for corruption and decay in the Buddhist hierarchy and monkhood in the latter part of the ninth century onwards. It even led to the formation of monk-soldiers (sohei). From defensive these sohei became offensive intimidating the national government. The power of the sohei became so unmanageable that the Fujiwara clan had to bring in provincial warriors to put down the sohei in the 11th century. The military finally established a military government in Kamakura near Tokyo in 1185.

Buddhism was transformed visibly. The three new forms of Buddhism, Jodo Shin, Zen and Nichiren were established in the 13th century. Now only simple piety and spiritual excises prevailed. So finally personal experience, piety and intuition were the mainstay of the religious practice. In this period all classes including the common people came to abide by the new Buddhist schools. Buddhism for the common man was now available to layman or monk, man or woman.

What is Zen Buddhism?

Let us start with the question: “who is the founder of Zen?”

Bodhidharma came to China in the 6th century and it was he that was generally credited as the founder of Zen. Some say that this was not the case. They say that Huineng was the real founder of Zen in the 8th century. Huineng’s enunciation that prajna and jhana should go together and that one should not practice jhana first until proficient was a startling reversal to the previous Patriarchs. One cannot have jhana without prajna and vice versa. Prajna is intuitive wisdom, which is equivalent to enlightenment.

The Noble Eightfold Path is composed of three disciplines: 1) moral precepts, 2) meditation (jhana), and 3) prajna (transcendental wisdom). So with Huineng’s teachimg, prajna (enlightenment) is synonymous with jhana (meditation). This is Zen Buddhism. Whereas before Huineng, meditation comes first, and when meditation succeeds wisdom and enlightenment arise. But prajna cannot be attained with discursive knowledge. It is intuitive knowledge. In other words, while we are thinking, talking and feeling, Zen and prajna are present at the same time. Zen and prajna are not two different items: they are one and the same thing. When one sees a flower, the flower must see one as well. This is then the real seeing. Also knowing alone is not enough. Seeing must come with knowing: seeing is direct experience and knowing is philosophical, knowing about. So in Zen context, the seeing and knowing must move up to a higher plane, and this intuitive seeing becomes prajna, which is jhana. When Zen talks about feeling and desire it should be reminded that these feelings should not refer to the selfish relative self. It should refer to something higher, so that it becomes intuition---enlightenment. It must also be collective or total intuition, which becomes real understanding of reality i.e. enlightenment. This is what Zen tries to achieve. In practice, Zen means doing anything perfectly: making mistakes perfectly etc. In other words, there is no egoism in what we are doing. The whole activity is harmonious. The perfect pain that we suffer is universal pain. The joy is universal joy.

Zen has no dogmas, no ritual, no mythology, no church, and no holy book. In all its varied and deep experiences of life and culture, there is usually a similar taste of depth of oneness. But there is also separation. Egolessness and ego are also absorbed in this depth of voidness. Zen is interesting and has good taste. Its mountains are more mountainous. Actually nobody understands Zen. Nobody can explain it. Zen arises spontaneously out of the human heart: not a special revelation to anyone. When goodness, truth and beauty are all present, as one, there is Zen. To grasp movement in stillness, and stillness in movement, this is Zen.

Sunyata

Another crucial statement of Huineng is “Fundamentally not one thing exists” confirms the sunyata (emptiness) of the Wisdom Sutras. This emptiness affirms the ultimate reality that lies beyond all concepts. It also accords with the philosophy of Nagarjuna, which is not nihilism. Huineng’s enlightenment can only be realized when one’s consciousness breaks through rational and dualistic thinking. Nothing is grasped because prajna (wisdom) works in a non-objective way. This is the true, free, dynamic mirror-play of the mind.

In the Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, the two types of meditation are exemplified very discriminatively by the two Chinese phrases: k’an-ching (kanjo) and chien-hsing (kensho). K’an-ching means “paying attention to purity”, and chien-hsing means “seeing into one’s true nature.” Paying attention is an ego effort, whereas seeing into one’s Buddha-nature is transcendence. There is a world of difference here. In the quiestistic type of meditation, one must continually wipe clean the obscurities, whilst seeing into Buddha-nature the dust on the mirror is not a hindrance. In this latter case, non-dualism has already been achieved. In Huineng’s teaching, dyana and prajna are the same thing i.e. practice and enlightenment are identical. So meditation here means that it is only a process of revealing one’s enlightenment: it is not indispensable to attaining enlightenment. That is why Huineng had no specific methods of meditation. There is a great deal of freedom and leeway in his meditation techniques. He warned against motionless sitting because it would obstruct the Tao, obscuring true reality. In paying attention to purity externally, one only inhibits his original Buddha-nature, because one’s inner nature is not activated.

Buddha-nature

The Doctrine of No Mind

Nagarjuna in the school of the Middle Way postulates in the Diamond Sutra the theory of Voidness. Enlightened seeing is non-seeing, knowing is non-thinking (wu-nien), mind is no mind (wu-hsin). D.T. Suzuki uses the word “unconsciousness” to embrace the whole concept. His Zen Doctrine of No Mind signifies the ultimate reality with terms like “non-thinking, non-form, no mind, suchness, Buddha-nature etc.” In the same study, Suzuki said “self-nature which is self-being is self-seeing, that there is no Being besides Seeing which is Acting, that these three terms Being, Seeing and Acting are synonymous and interchangeable.”

Similarly, the sutra of the Sixth Patriarch reads: “…in this teaching of mine all have set up no-thought as the main doctrine, non-form as the substance, and non-abiding as the basis. Non-form is to be separated from form even when associated with form. No-thought is not to think even when involved with thought. No-abiding is the original nature of man.” In Huineng’s Southern School of enlightenment it is an experience of ultimate reality and of Transcendence and Being. This breakthrough of duality brings the yogi to a new dimension of Being and Transcendental Unconsciousness. Thomas Merton puts it very well: “It really makes no difference whatever if external objects are present in the mirror of consciousness. There is no need to exclude or suppress them. Enlightenment does not consist in being without them. True emptiness in the realization of the light of prajna-wisdom of the Unconsciousness is attained when the light of prajna… breaks through our empirical consciousness and floods with its intelligibility not only our whole being, but all the things that we see and know around us. We are thus transformed in the prajna light, we ‘become’ that light, which in fact we are.”

Buddha-nature is not the soul. It is not consciousness. It is not the storehouse consciousness (alaya-vijnana). Dogen: ‘For all beings are Buddha-nature.” It is part of all beings or everything that exists. This includes humans, animals, plants and inanimate objects. The Avatamsaka Sutra says:

The three worlds are One Mind,

Nothing exists outside the mind.

Mind, Buddha, and all living beings----

There is no difference between these three.

The three worlds are---- the world of desire, the world of form and the world of formlessness. These signify the entire universe, the totality of physical and mental reality. When one is enlightened, when the mind is awakened with practice and nirvana is reached: ‘the mind is identical with Buddha.’ Also, “Buddha-nature is all things.” All beings are Buddha-nature to the same extent. The one Buddha-nature is completely there in every moment. Buddha-nature does not manifest in a continuous series of past, present and future.

One cannot see, hear or know Buddha-nature with one’s eyes, ears or mind. Buddha-nature is open, vast, empty and lucid. The ground of the nothingness of Buddha-nature is emptiness. The nothingness of transcendence is a double weighted “absolute emptiness.” So the being of Buddha-nature is synonymous with nothingness of Buddha-nature and emptiness of Buddha-nature.

As everything in the universe is impermanent, so is Buddha-nature. There is permanence only in becoming, but supreme enlightenment and Buddha-nature are all impermanent. Zen enlightenment is an experience of oneness (non-duality). Ma-tsu states:

Outside the mind there is no Buddha,

Outside Buddha there is no mind.

Do not cling to good, do not reject evil!

Purity and defilement, if you depend on neither,

You will grasp the empty nature of sin.

In every moment it is ungraspable,

For no self-nature is there.

Hence the three worlds are only mind.

The universe and all things

Bear the seal of the One Dharma.

Our mind is originally one with the Buddha’s i.e. our Buddha nature. To the Zen Buddhists, Buddha nature is first and the historical Buddha is second. In order to realize our Buddha-mind, one must practice zazen wholeheartedly. It also must include every action, speech and thought in our daily life. This Zen way of life would lead to satori or enlightenment, but satori is not the main aim. According to Dogen, meditation practice is enlightenment itself. It is told that meditation (zazen) is the main and crucial practice of all Zen Buddhists, but the Koan is also of prime importance to the Rinzai sect.

Rinzai Zen

The Rinzai sect also practices meditation, but more importantly is the Koan. The meditation methods used usually vary from master to master, and there is a fair amount of freedom in their methods. Whereas Soto Zen practices mainly zazen and mindfulness of daily activities. Eisai-zenji (1141-1215), founder of the Rinzai sect, went to China to study Zen at the age of 28, but he was not enlightened in this first attempt. At 49 he went to China again and this time he was successfully enlightened. He was then able to transmit the essence of Lin-chi (Rinzai) to Japan. He taught strict adherence to the vinaya, the rules of discipline for the monks and nuns. This is of the utmost importance. Zazen is secondary. He also taught that dharma, the Buddhist teachings of Law were identical to the Buddha-mind. And in order to realize the Buddha-nature, the sutras are quite useless unless one is already realized. That means Buddha-mind is transmitted from Buddha to Buddha. We are already Buddhas when born, but we do not realize it. The Rinzai method of using koans is to progress step by step in one’s meditation. Koans get more and more difficult as one goes on until one is enlightened.

The Koan

The practice of koans is unique in the practice of religions of the world. Near the end of the T’ang period the Zen masters evolved this technique leading to enlightenment. Ruth Fuller Sasaki who was married to a Japanese Zen master, had this to say about koans: “The koan is not a conundrum to be solved by a nimble wit. It is not a verbal psychiatric device for shocking the disintegrated ego of a student into some kind of stability. Nor, in my opinion, is it ever a paradoxical statement except to those who view it from the outside. When the koan is resolved it is realized to be a simple and clear statement made from the state of consciousness which it has helped to awaken.”

The psychological sequence of the koan practice.

Nan-yuan Hui-yung (d.930) was the first to apply the words of earlier masters as a mondo (exchanges of master and disciple) in a quick and direct way. The koans consist of sharp retorts of masters, anecdotes from the daily life of the Zen monastery, and occasionally even verses from the sutras. The disciple is given a koan to solve by concentrating continuously with all his energy until he loses rational thinking. In this heightened atmosphere he breaks into the suprarational realm of enlightenment. Heavy concentration on the koan, day and night, will finally land the practitioner into a hyper-alert state, in which he is aware of only one thing---the koan. At first he searches for a solution of the koan, to no avail. Then he reaches a state of helplessness and he finds himself climbing up the wall, looking for the door of exit. Again it is useless. He has to have an about turn sometimes leading to a psychic explosion. The master is always there to guide and to lead the disciple. This master-disciple relationship is close and intense, like the guru in India. There are daily interviews with the student’s reports of makyo (hallucinations), his desperateness with corrections and guidance by the master. Whatever happens, the student is further exhorted to continue to work harder until the glimmer of light begins to appear. Thence to satori.

The Chinese word for koan is kung-an. It means ‘public announcement.’ It is generally accepted that there are 1,700 cases of koans, but there are probably many more. The best known are the Hekiganroku and the Mumonkan of the Sung period. The hundred cases of Hekiganroku paint a vivid picture of the koan world and the Zen movement in China. It is of superb literary spiritual quality. The Mumonkan collection of forty-eight koans is simpler, more for practical use. These were compiled by Hui-Kai (1184-1260) a hundred years later. The Zen masters seemed to prefer the Mumonkan precisely for their simplicity.

Soto Zen

Dogen introduced Soto Zen to Japan in the early part of the Kamakura period (1185-1336). Soto Zen says that meditation awakens the individual to the fact that he is already and totally integrated to the Law of Buddha (i.e. enlightened), and meditation is to realize his inherent Buddha-nature. This principle of non-duality is known as Madhyamika in Buddhism. It states that thoughts of duality (subject-object, being and non-being etc) cannot arrive at the true nature of existence. The Madhyamika states that there are two levels of truth: the ‘supreme’ and the ‘conventional’. The supreme means insight into the transcendental, where sunyata (void or emptiness) dissolves the opposites. In this void, opposites do not cause any dichotomy, as they are complementary entities in the existential world. One is all and all is one. The conventional truth however points to insight into the phenomenal, which refers to the cause and effect in the doctrine of dependent origin. So Dogen’s Madhyamika is the practical application of non-duality.

Soto Zen states that Buddha-nature is inherent in our mind and the practice of zazen is merely to realize this inherent Buddha-nature. One cannot acquire it. In this context, zazen practice is an act of enlightenment.

Seeing that Buddha-nature is universal, all men are equal with regards to Buddha-nature. Zen is therefore not an analytical philosophy but an experiential one. It also follows that man has to work, and Zen values labor in the individual practitioner. Zen consequently emphasizes harmony with the environment, which is cultivated by man on nature. This also symbolizes the Bodhisattva path, which helps to alleviate the problems of other sentient beings. Zen does not allow the life of a hermit in which the suffering of others is excluded.

Dogen

Dogen was born in Kyoto to an aristocratic family in 1200. His father was a high-ranking government minister. At the age of four he was able to read Chinese poetry and by the age of nine he read a Chinese translation of the Abhidharma. However his childhood was marred by the deaths of his father at two and of his mother at seven. These losses made him want to find out the meaning of life and death. Thus his determination to join the monkhood. Early on he taught that one should not squander away one’s transient life, and no amount of power and wealth can prevent death. We can only take with us at death our karma.

He became a monk at the age of thirteen at Mount Hiei, the headquarters of Tendai Buddhism. For the next several years he studied Mahayana and Hinayana Buddhism under his master, Abbot Koen. His main conundrum was that “if all of us are endowed with Buddha-nature, why is it so difficult to realize it?” He went to many monasteries to ask this question, but none could provide him an answer, until he came to Eisai at Kennin-ji. Eisai’s answer was that all the Buddhas themselves do not think of Buddha-nature, but only the grossly deluded ponder over such problems. This assuaged Dogen to some extent. He decided to stay with Eisai and learn his Rinzai teachings, but Eisai died the next year.

After this he studied for nine years under Myozen (1184-1225), who was a disciple of Eisai. Under Myozen he learnt all the methods of the Rinzai sect. After so many years under Myozen, Dogen is still unfulfilled. Then he went to China with Myozen in 1223 to further study Zen Buddhism. After arrival in China, he stayed on the ship for sometime. It is in this ship that he learnt from a tenzo-monk, who was a cook of a large monastery that Zen must be expressed through our daily actions, be it cooking, cleaning or sewing. He went to T’ien-t’ung monastery and trained under Abott Wu-chi. It was here that he was discriminated against because he was a foreign monk. His protest against this racial discrimination was not heeded. It was only after he appealed to the Emperor that this racial discrimination was redressed. In spite of this, his understanding of Zen deepened. When Abott Wu-chi died he came back to China to study under Abott Ju-ching. The latter taught him to practice zazen day and night without stop. Then one day he heard Ju-ching admonishing a fellow monk next to him dozing off. “In practicing zazen, body and mind have been cast off; you cannot attain it by sleeping!” With this admonishment, Dogen became fully enlightened. He continued to stay with Ju-ching for another two years, for practice after enlightenment is just as important as before enlightenment.

In 1227, he decided to return to Japan. On returning, he was disappointed by the standard of practice in his old temple, Kennin-ji. So he moved to An-yo-in temple. Here he wrote “A Universal Recommendation for Zazen”, which teaches correct zazen and essence of Zen Buddhism. It was also here that he wrote “The Practice of the Way”, which was the first section of his great master-piece, the Shobo-genzo.

When he moved to Kosho-ji temple, he had his first meditation hall built for monks and lay people alike. At the same time he warned against building fine temples and carving of Buddha images. When this hall was built, his reputation became so popular that the hall was too small when it was completed. He had to start a new hall.

The two main points of Dogen’s teachings are 1) there is no difference between zazen and enlightenment, maintaining that zazen itself is an enlightenment practice and 2) right daily behavior is Buddhism itself. However, he also stressed the importance of the sutras, which he taught to be one with Truth. He also opposed koan practice. Nonetheless, even to this day, some Soto masters still teach the koan practice

These are nine points that can be extracted from Dogen’s thought:

1. Identity of self and others. Zazen is the complete realization of self, identifying with others. He said: “To study the Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things. To be enlightened by all things is to remove the barriers between one’s self and others.”

2. Identity of practice and enlightenment. There is no difference between practice and enlightenment. There should not be any attachment to the outcome of the practice.

3. Identity of the precepts and Zen Buddhism. Novice monks must know the 16 Bodhisattvas precepts before becoming monks. There is no difference between the precepts and Zen itself. When enlightened he is already endowed with the precepts.

4. Identity of life and death. Although most people love life and hate death, nobody can avoid death. Once you come to terms with death, there is no life or death to love or hate. Both are part of the life of a Buddha.

5. Identity of time and being. Time is being and vice versa. Time can only be experienced but cannot be cognized. Now is now which includes past, present and the future. Without now there are no others. Now is absolute and eternal. Once lost it never returns. So practice continuously without delay.

6. Being and nonbeing. Nonbeing is not “nothing.” It is being and vice versa. In non-dualistic terms, both are absolutes. So we have both the Buddha-nature and we also do not have the Buddha-nature in non-dualistic viewpoint. Nonbeing in Zen is never the nothing of nihilism but it is a lively and creative function of the Way.

7. Men and women. There is no gap between right and wrong, clever and foolish, high and low social status, or men and women. All can realize Buddhahood. The Way is open to men and women equally.

8. Monks and lay people. Both can practice, but monks are free from world affairs. Lay people can pursue the Way but their practice must be intense and persistent. Of course the best is to become monks and follow the precepts. Remember Dogen’s teaching is that practice takes precedence over theory.

9. Sutras and Zen Buddhism. The Way of the Buddha-mind is beyond letters and sutras, because attachment to the letters and sutras is itself a hindrance. So it is the attachment to the letters and not the letters that must be cast away.

To Dogen the practice of zazen is of prime importance. He advised: “You should cease from practice based on intellectual understanding and pursuing words. Instead turn inwards and illuminate your self. Body and mind should drop away, and your original face will be manifest. If you want to attain suchness (Buddha-nature), you should practice suchness without delay.

His instructions are: One should sit on two cushions, placed one on top of the other, in a quiet room, in the full or half lotus position, the left hand placed on the right, thumb tips touching. Thus sit upright in a correct bodily posture, neither inclining to the left nor to the right, neither leaning forward nor backward. All efforts should be directed at overcoming the inner unrest that arises from discursive thinking. Cast aside all involvement and cease all affairs. Do not think good or bad. Do not administer pros and cons. Cease all the movements of the conscious mind, the gauging of all thoughts and views. Have no designs on becoming a Buddha. This has nothing to do with sitting or lying down.

This … is the essential art of zazen…..It is simply the Dharma-gate of repose and bliss. This practice requires a great deal of effort. It must be persistent.

Zazen is enlightenment according to Dogen, when body and mind (ego) are cast off. His first satori came when he heard Ju-ching admonishing his fellow monk in China about sleeping. This satori was the result of casting off of the ego from his consciousness, and this memory remained with him for the rest of his life. This is his conscious and luminous experience of enlightenment perceived in zazen. He had broken into the non-dualistic Unconsciousness of Buddha-nature. Thus satori is an experience of Being. This is his “taking one step beyond the top of a hundred-foot pole”, when his normal consciousness is released and transcended during zazen. Dogen formally instructed his students with this: The most important point in the study of the Way is zazen. Many in China gained enlightenment solely through the strength of zazen… The Way of the Buddha and Patriarch is zazen alone. When asked about the value of sutras, he retorted: “Even though you study a thousand sutras and ten thousand sastras and sit so hard that you break through the zazen seat, you cannot gain the Way of the Buddhas and the Patriarchs without this determination to cast off body and mind, which is the very quintessence of being enlightened.

He again said: “In the Buddha Dharma, practice and realization are identical. Because one’s present practice is practice in realization, one’s initial negotiation of the Way in itself is the whole of original realization… As it is already realization in practice, realization is endless; as it is practice in realization, practice is beginningless.”

This view shows that satori is a shining forth of Buddha-nature. Achieving of satori is not the end. Practice must continue after satori because it is practice in enlightenment, which must be continually confirmed by practice. Therefore his shikantaza (merely sitting) is the fullness of the Buddha-way

Satori

Satori is enlightenment. It is the breakthrough from this dualistic world to the non-dualistic realm of Reality. This is the goal of all mystics of all religions. When one is in that realm, there are signs and symptoms pertaining to that state. However, it is ineffable in that when one returns to dualism no words can describe that state. There are, however, mental, psychological, emotional and physical signs that do not come close to presenting the actual Ultimate State of Consciousness. The Ultimate State of Consciousness is superbly glorious with bliss, joy and happiness co-existent with calmness, serenity and tranquillity.

Firstly, there are physical signs of approaching satori, but not the real thing. Heat, vibrations up and down one’s spine, trembling all over the body, pain, sometimes excruciating, are some of the premonitory signs. Then the feeling of lightness, as if one is floating in the air. Makyo, in the form of hallucinations and visions are rather often, especially after prolonged and intensive meditation. Some truly go into psychotic states. Makyo must be recognized and stopped by the master or else the disciple is led up the garden path and indelible damage is done. This is because the student thinks he is being enlightened. Zen masters call them “devil’s realm.” Then the surest one is Light: all objects in the room and the room itself are lit up as if a search light is blasted on to everything in that room. If other people are present in that room sometimes some of them can also see the light. Students also experience different colored lights and all modes of sound and music. Visions of Kuan Yin, Buddhist saints and Buddha himself are not uncommon, leading to this advice: “If you see the Buddha, kill him!” All these devil’s realms must be apprehended by the master, who will lead the practitioners back to the path. Also pain is not an infrequent symptom. Sharp, piercing pain like being stuck with needles up and down the spine is also a common symptom. When satori breaks through there is a great sense of joy and happiness. They laugh out without any control. They also cry for happiness. They dance and they sing on top of their voices. There is a freedom that is equivalent to being let out of prison after decades of incarceration. Of course the liberation is much more exhilarating than a breakout from prison.

Cosmic consciousness The nearest comparison to satori is a glimpse of cosmic consciousness. Here in the Zen context, the most frequent exclamation is “nothingness.” Every thought, every vision, every master, every concept is transformed into nothingness. Before this breakthrough there is high tension. There maybe lights or maybe total darkness. Then abruptly the infinite space turns into nothingness. Or ‘I and the universe are one’ is a common comment. This breakthrough may be precipitated by a sound caused by a pebble striking a bamboo or a striking of a clock or a shout by the roshi. After the enlightening episode, the practitioner is a bit confused and absent-minded. He needs some time to adjust, to shout or cry it all out. Of course he also needs to have confirmation by the master.

These satoris may start with a weak one at first. Then they are repeated again and again, each one stronger than the previous one. These mini-satoris gather strength as they practice into full fledge satoris. The final one is the maha-satori. From thence onwards, there is no more doubt and not the slightest chance of retracement. He is now established in that state of enlightenment but he has to continue to practice. This enlightening practice of zazen has to continue until death. However, he is now endowed with Buddha’s Eight aspects of Enlightenment, which lead to Nirvana. These eight aspects are: 1) Freedom from greed 2) Satisfaction with whatever he has 3) Quiet and solitary life. 4) Diligence. 5) Right mindfulness. 6) Samadhi: to remain undisturbed. 7) Wisdom for self-reflection. He has now the power to see the Truth with his naked eyes. 8) Freedom from random discussions and thoughts.

There are many more books one can read on the subject of Zen. If interested one can go to individual masters like, Matsu, Huang-po, Hakuin, Harada and Yasutani. For English readers, Dr. D.T. Suzuki (1870-1970) is a must. He himself was enlightened as a member of the Rinzai sect. With his exquisite knowledge of English, his analyses of Rinzai Zen are superb to say the least.

Bibliography

1. Aitkin, Robert. Taking the Path of Zen. North Point Press. 1982.

2. Blyth, R.H. Zen and Zen Classics. Vintage Books. 1978.

3. Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Enlightenment. Weatherhill. New York. 1979.

4. Cleary, Thomas. The Original Face: An Anthology of Rinzai Zen. Grove Press inc. N.Y. 1978.

5. Cleary, Thomas. Records of things heard (talks by Dogen). Prajna Press Boulder. 1980.

6. Cleary, Thomas. Timeless Spring. A Soto Zen Anthology. A Wheelwright Press Book. 1980.

7. Harada, Sekkei. The Essence of Zen. Kodansha International. 1993

8. Red Pine, translated by. The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma. North Point Press. 1987.

9. Suzuki, Shunryu. Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. Weatherhill. 1976.

10. Suzuki, D.T. The Awakening of Zen. Prajna Press. Boulder. 1980.

11. Suzuki, D.T. What is Zen? The Buddhist Society, London. 1971.

12. Suzuki, D.T. Living by Zen. Rider and company. 1972

13. Suzuki, D.T. The Zen Doctrine of No Mind. Rider and Company. 1969.

14. Yokoi, Yuho. Zen Master Dogen. Weatherhill. 1976.

![]()